In 1990, Congress passed the Judicial Improvements Act, ushering in a new era of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR).

Sold to the public as a way to reduce court congestion and streamline justice, ADR was supposed to make the legal system faster, cheaper, and less adversarial.

But beneath the surface, a different transformation was underway.

Instead of shrinking, the federal judiciary exploded in size and footprint — launching the largest courthouse construction boom since the New Deal.

Between 1990 and 2010, the U.S. government spent over $10 billion building more than 50 new federal courthouses and expanding over 60 more, according to records from the General Services Administration and the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Far from reducing space needs, the judiciary tripled its occupied square footage between 1990 and 2010 — a growth rate unmatched in previous decades.

If ADR was about reducing litigation, why were more courthouses needed than ever before?

The answer points to a bait-and-switch at the heart of modern judicial reform.

Courthouses Reimagined: From Trial Arenas to Administrative Complexes

Rather than bustling centers of public trials, the new courthouses were designed to accommodate a different kind of business:

- Private mediation sessions

- Settlement conferences

- Compliance hearings

- Special masters proceedings

- Managerial judging — where judges oversee case management instead of presiding over trials.

According to court reform scholars like Judith Resnik and Marc Galanter, ADR practices led to the phenomenon of the “vanishing trial.”

Trials in federal courts dropped dramatically during the 1990s and 2000s — even as total case volume continued to rise.

What replaced public trials was a vast administrative processing system, handling disputes through negotiation, compliance, and settlement without ever reaching a jury.

The Administrative Empire: Expansion, Not Efficiency

The explosion in courthouse construction wasn’t about improving justice.

It was about retooling the judiciary into a high-volume administrative empire.

With each new courthouse came:

- More rooms for confidential mediation instead of public trial.

- More administrative offices for compliance monitoring.

- More judges and clerks managing settlements, not adjudicating rights.

While traditional courtroom trials dwindled, the operational budgets of federal courts grew — fueled by increasing grant funding, administrative positions, and infrastructure spending.

Critics argue that what was framed as “reform” was, in reality, a quiet expansion of federal control over civil disputes, turning the judiciary into a hybrid administrative regime rather than a constitutional court system.

The Hidden Costs of “Efficiency”

The consequences of this shift are profound:

- Reduced transparency, as more cases are resolved behind closed doors.

- Diminished constitutional protections, with fewer trials and more “managed” outcomes.

- Greater bureaucracy, as court cases became compliance files instead of truth-finding missions.

And despite the massive investments, today’s court users still face backlogs, rising costs, and delayed justice — even as mediation and case management dominate the docket.

Conclusion: Reform or Power Grab?

The 1990s judicial reforms promised efficiency.

What they delivered was a $10 billion expansion of administrative power, hidden behind the language of “alternative resolution.”

Instead of fewer cases, we got more bureaucracy.

Instead of public trials, we got private processing.

Instead of streamlined justice, we got an empire of compliance — and a judiciary that grew larger, richer, and less accountable in the process.

The real “alternative” turned out to be an alternative to constitutional due process itself.

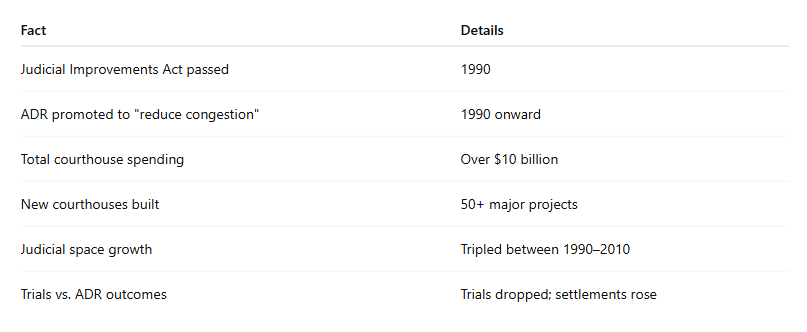

Sidebar: Quick Facts